Studio Visit: Matthew L. Rossi

by A.L. McMichael

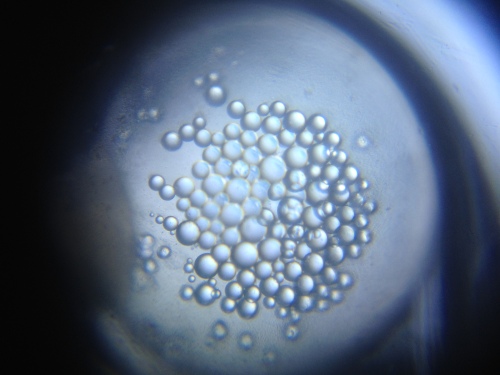

“Minnow Egg” taken May 2015.

There’s a table in Matt’s apartment on which generations of Rossis have rolled out the family ravioli recipe, where he composed twelve short stories that encompassed an MFA thesis before tackling several hundred pages of a novel, and where an electric kettle boils water every morning for the French-press coffee maker sitting beside it. I know all of these things because I share the kitchen where this patinaed wooden surface is positioned between two windows. The view is of urban backyard gardens and the Empire State Building, its spire a glowing beacon after dark. Over the last few months, though, the table’s role has morphed from office to laboratory to studio. The growing body of photographic work Matt does there captures dozens of miniscule flora and fauna, the kinds of lives I probably unknowingly squash with a flip-flop on any given trip through the yard.

Matthew Rossi’s handcrafted field microscope, with water from a Brooklyn creek and assorted found objects. (Photo: A.L. McMichael)

“What looks to the naked eye like a jar full of mud is teeming with little creatures,” he asserts with the glee of a kid returning home from summer camp. Sure enough, a tiny sac of minnow eggs looks like a submerged trove of pearls in the blue light of his microscope camera (top photo). Indeed, the visual effects of his nature photography are surprisingly sophisticated, a powerful harnessing of cardboard, e-waste, and nature’s detritus. To record these images, he created a field microscope using the lens from a CD-ROM drive mounted to discarded computer packaging in order to see a nearly-invisible creature by viewing it on an iPhone screen through its camera. The glass microscope slides are backlit by an LED bulb from a bicycle safety light (a process akin to shooting on a lightbox), lending the subjects an ethereal affectation and often constraining the picture frame into a circle. From there, Matt composes larger-than-life photographs of the minuscule world.

“Amphipod,” photo of a crustacean from Sea Isle City, NJ.

An image of an amphipod’s veins and surfaces (above) recalls the velvet richness of chiaroscuro paintings, wherein shapes and stories emerge from darkness. The resulting aesthetic lies somewhere between Man Ray’s minimalist surrealism and the fervor of a Goya etching. But to me the subject matter also calls to mind Northern Renaissance artists’ social commentary embedded into paintings—references to death, redemption, and new life emerging in the painstaking accuracy of depicted flora and fauna—and I’m tempted to silently salute Rachel Carson with every newly identified citizen of the ecosystems in Matt’s photos. The amphipod’s delicate lines are striking against the deep ocean of bokeh. There’s both serenity and danger in this velvety deep. The paper-thin slides on which it swims are in sharp contrast to the vastness of oceans and rivers where such creatures live.

Nature photography like this is an art of transformation, relying on changes in scale, in light. The act of seeing the invisible and reframing it at such a vastly different scale, “strangely opens up the world in a way [that is] different than other things I have experienced,” Matt explains. Creatures like vorticella (protozoa) are “not hanging out, but forming gelatinous structures.” He continues, “I think of them as floating mind-maps.” Their cilia (tiny, moving hairs) move all the time, catching occasional prey while colonies of vorticella seem to the untrained eye to be simply hanging out in the water.

He likens describing the natural world to analyzing formal elements in art: “When you blow up their world to our size, you get texture. You get clusters. [The plants and animals] have structures.” When he invites a formal analysis of nature itself, as well as the photographic context in which it’s captured, historical nature writers like Charles Darwin and John James Audobon reverberate in the work. To Matt, part of the naturalist’s role is to recognize and identify the inspected creatures, giving them a certain dignity. A brownish grey moth wing is “unremarkable at a distance” but, under the microscope, it has textured “brushstrokes,” and scales become an assembled series of gradient browns with the dimensionality of little structures that assemble themselves into an insect. The arrangement of cells in a leaf reveals “how much more textured the world is than what we see.”

One outcome of this kind of sustained formal analysis and appreciation is a responsibility and empathy for the unseen, a recognition that we are part of a larger universe. Matt cites Neil DeGrasse Tyson’s Radiolab talk, “Space“, on how the telescope opens up the vastness of the universe to humans, who become the microscopic creatures in that equation. He also counts Timothy Morton’s ecocriticism as influence toward the conflation of art and science to drive that conversation. He’s fond of using Morton’s term “Earth magnitude” for the notion of thinking about things “on a scale so much larger than you can conceive of,” like Morton’s example of systems as objects, or for thinking of a species as it exists as a continuum.

One half-joking series of inquiries is what Matt has christened, “Things That Peeve Me,” which looks at mosquitoes, pollen, mold, and the like. He performs a style of catch-and-release photography for it, wherein he examines the offending creatures and then lets them go, either back into a little tank or their original habitat. Tormented by mosquitoes all summer, he finally captured a larva, which will have a chance to “grow into a mosquito, which I will put outside.” I pressed him a bit about the altruism toward predatory insects: “Looking at it in this form is different,” he argues, because there’s a difference between a pest in a pot of dirty water and an animal with a functioning digestive tract. “I see it contract, responding to me,” so that it’s “not just eating me, but me-sized.”

“So, are you on equal footing as creatures?” I ask.

“Well,” comes the response. “It’s like me in some ways, but really nothing like me.” The larva in question squirms away, its muscles contracting. Indeed, in a video of mosquito larva, the sounds of life in our apartment—water running, background music, our yowling and impatient housecat—highlighting that the ecosystem we call home includes constant imposition of the odd and invisible.

The natural world maintains its own agency in the workflow, one in which images and movements are revealed to the photographer rather than him manipulating a preconceived subject. Matt does not always know what’s in the water or mud before it hits the slide. The creative output, then, is an ongoing documentation of investigating nature, channeled into a series of images selected to represent that process. What the eye sees through a microscope is incredibly hard to capture, making the photographic process a return to the seeming randomness of the found object in nature. In defining art as finding new ways to see or represent something, harnessing the power of tiny lenses to illuminate and magnify becomes a deeply investigative creative process.

This studio visit took place June 14, 2015. For more of his photographic work, see Matthew Rossi’s Vimeo stream. You can read his contributions to the Foldscope Explore: Exploring the Microcosmos community online, including the essays, “Why, As an Artist, I’m Excited About the Foldscope,” “A Model Creature: A Complete Drosophila Life Cycle,” “In DUMBO,” and “The Itch Part Two.” To chat with him on Twitter: @mlrossi80.