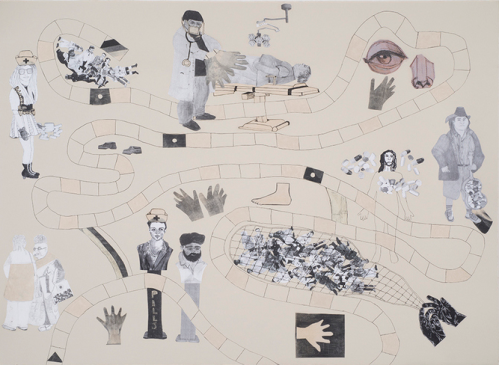

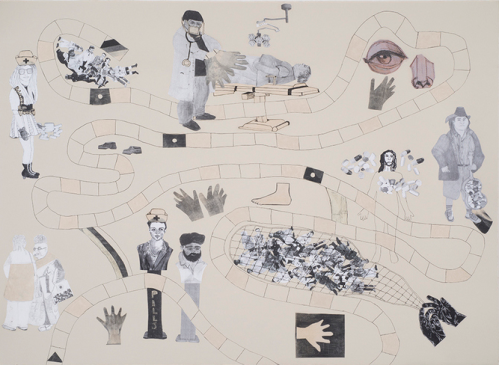

The Safety Net, mixed media collage, 2015

Manual Realizations: Leslie Kerby’s The Laying On of Hands

Working always deftly and fluidly among a full range of image-making techniques, including drawing, painting, printmaking and collage, and recently adding sculpture and animation to her practice as well, Leslie Kerby creates all manner of visual narratives addressing, with a keen critical eye, societal practices, ills, curiosities, complexities, services, interactions and constructs. With palpable sincerity and a sense of humor, she has addressed many facets of our politically circumscribed, socioeconomically determined or determinable lives, from the neighborhoods we live in to the ways in which we attain our goods and services, from the ways in which we communicate with one another to the cemeteries where we might visit or bury our loved ones. Kerby has never shied away from handling even the most controversial or aesthetically challenging themes. Indeed, the most difficult ones sometimes become the greatest conduits for her creative impulses.

This is certainly the case with The Laying On of Hands, one of Kerby’s most recent and materially polyphonic bodies of work. Here, the artist turns her critical eye towards one of the most politically charged, ideologically divisive, societally expansive and, at the very same time, most deeply intimate issues of our time in the United States: our healthcare system. Kerby began contemplating this as subject matter six or seven years ago, having personally experienced, endured or witnessed no shortage of the good and bad of how we insure ourselves for and possibly receive medical care. She knew that, in a few ways, the system worked well enough. She also knew that, in many ways, it was direly inefficient, unnecessarily confusing and, for far too many people, devastatingly lacking. Given the issue’s gravity and complexity, however, Kerby spent several years moving forward with other projects instead, all the while pondering how she might effectively convey her thoughts about the precarious, indeed fundamentally perilous state of our healthcare system in ways that would be both visually engaging and candid in commentary.

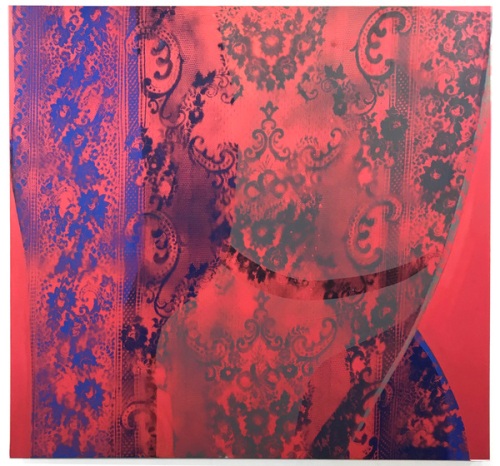

Blanket Coverage, mixed media collage, 2016

Kerby’s solution turned out to be simple and inclusive. She decided that works on paper with graphic immediacy would constitute the body of work, and that each work would itself be constituted by imagery produced via essentially all of her manual skills as a maker of imagery. In a way, just those few decisions are already striking analogs for what our healthcare system is definitively not, and what or how it could or should be: it is neither simple nor inclusive, but it certainly ought to be; aspects of it that might be conceptually plain are presented in ways that confound everyone, from doctors to patients and customer service agents; many of the system’s verbal convolutions are surely intentional, masking fees and exceptions in footnotes and conditional clauses; people at various income levels, especially the lower ones, as well as people who might already be sick are left out of the system entirely, or they are gravely underserved, meaning underinsured; and the system overall feigns personalized service while remaining pitilessly impersonal, removed, uncaring. Unfortunately, these are not new problems at all with regard to how healthcare in our country is provided, nor are they new in terms of how it is presented in our political discourse. Yet they are problems that have never gone away, and that seem to become worse as medical technologies advance, and as masses of data come to define patients and problems in general, statistically, rather than determining an individual patient’s problems specifically. This should seem absolutely paradoxical. It absolutely is.

How, then, do Kerby’s works convey something simpler, more inclusive, more comprehensible and intimate? How are the obvious levels — for they surely are obvious — on which our own lawmakers and doctors should demand — for they surely should demand — improvement from our ‘service providers’ made manifest in The Laying On of Hands? It couldn’t possibly be more genial or straightforward. Kerby conveys her commentary by crafting individually identified or identifiable patients and doctors, sometimes interacting with one another, sometimes only almost, and she does so by doing, as an artist, precisely what doctors have always done, and what so many of them still want and are trained to do: employ their full range of diagnostic reasoning and manual skills to care for one patient at a time, one ailing person at a time, as meaningfully and holistically as they can. Kerby achieves both ideals by tapping into the full extent of her creative skill set, employing several very manually driven processes of drawing, printmaking, collage and image transfers, among other approaches, to create variably pictorial contours and silhouettes of patients now ailing, now under examination, now being medicated, now ostensibly becoming their medications. Visages and figurations, and most certainly the omnipresent motifs of hands and eyes, predominate these engaging compositions in which pills, simplified x-rays and pieces of equipment factor as well, with backgrounds generally left blank or spare. In a formal sense, per her clear sources of inspiration and characteristic treatments, Kerby’s yields are images of great candor and immediacy, aesthetically steeped in various elements of German Expressionism and, with very fitting specificity, Neue Sachlichkeit — indeed, one might even identify in Kerby’s collages a rather seamless merging of the two readily distinguishable traditions, the latter’s germaneness here not incidental given the medical nature of some of its most historically trenchant imagery.

The Dispensary, mixed media collage, 2015

On that note, Kerby, with perhaps a knowing nod to Christian Schad’s The Operation, makes her doctors, nurses and medical settings very easy for us to recognize. But how to recognize a student or a journalist, a chef or a plumber? Kerby identifies her protagonists in her very own handwriting, their facial features often well delineated, their attire or other accoutrements pointing to their trades or occupations. What do we know of their ailments? We see where they are ailing by way of where she places their pills within their figurative contours, with their medications sometimes taking the shape of objects relative to their professions: the librarian’s pills are spread across two pages of an open book; the banker’s are arrayed in a way that suggests coins; the musician’s are shaped like a guitar; the lawyer’s medications quite meaningfully sit atop the plates of a dramatically unbalanced scale of justice. How to keep viewers engaged in a suite of societally critical, even perhaps thematically somber works might seem an additional concern, but Kerby has cleverly foreseen that, undercutting the potentially overwhelming gravity of her subject matter — who will listen if it’s all pain and trauma, or keep looking if it’s all shock and awe? — by intermittently cartoony renderings, exaggerated embellishments, caricatured features and physiques, and even a certain kind of mirthful array in her arrangements.

Seriousness and humor come into most succinct and critically significant confluence in works like The Dispensary, in which a doctor and two nurses are portrayed as busts atop Pez candy dispensers, and in Candyland, in which the artist reconfigures many of the characters and formal tropes from her entire body of work into a loosely rendered representation of the eponymous board game for kids. Kerby’s critique here is at once precise and expansive: while the game is intentionally structurally misleading, so to speak, and indirect and obfuscatory in the sweet, felicitous interest of childish fun, our healthcare system is all of the same, and then some, in the bitterly sickening interest of corporate greed; and while the composition and visuals indicate a game for kids, they also suggest the hardly outlandish notion that insurance providers and pharmaceutical companies, assuming that we’re all manipulable and naïve, are playing a game with our bodies and minds. A form of casual entertainment for children, here, is simultaneously legible as a system of physical and psychological entrapment for adults.

Candyland, mixed media collage, 2015

This kind of duality is also present in Kerby’s ultimate addition to The Laying On of Hands, a video animation, made in collaboration with designer Lianne Arnold, in which the full set of collages undergoes, or even performs on itself, a kind of surgery, autopsy or anatomical investigation. Here, by laying her hands back onto or into her body of work, she quite literally quickens it, sets it into motion. Now her compositions come alive and interact with one another, and pieces from one wander about from one spot to the next, from one collage to the next. In this animated context, however, the child/adult duality Kerby implies in Candyland is essentially inverted. Now, a system that is often entrapment for adults becomes, in a delightfully rendered ‘cartoon,’ something that could readily entertain children. It’s hard to overstate the importance of Kerby’s dual modes, or even dual moods, in this thoroughly considered body of work. On the one hand, they help her engage viewers more broadly and permit certain aesthetic freedoms, from ‘fun’ images like candy dispensers to a rather graphically lighthearted animation. On the other hand, Kerby’s dualities also relate quite plainly to the great paradox of our healthcare system overall — that the very form of ideally pathos-driven, human-to-human interaction that should be most intimate, personalized and hands-on so often seems, thanks to corporate avarice and legislative apathy, as insensitive and impersonal as can be.

By tapping into so many of her artistic skills, sources of inspiration and critical modes in the creation of The Laying On of Hands, Leslie Kerby has crafted one of her most fully realized, conceptually seamless bodies of work to date. As you follow the trajectories of figures and forms from one mixed media collage to the next, and from the suite of collages to her video animation, you can’t help but find yourself in agreement with both sides of her implicit claim: staying alive and well truly should not be a roll of the dice, yet what our ailing healthcare system has let it become is a baffling game that toys with our lives.

________________

This essay was composed for the catalogue accompanying The Laying On of Hands, Leslie Kerby’s solo exhibition at Project ARTspace, located at 99 Madison Avenue in New York City. The show will be on view from 16 May to 15 June, 2018. More information about the show can be found here. Images courtesy the artist.

Paul D’Agostino, Ph.D. is an artist, writer, translator, curator and professor living in Bushwick, Brooklyn. More information about him is available here, and you can find him as @postuccio on Instagram and Twitter.