Embodiments

by Paul D'Agostino

Embodiments: Exquisite Corpse

Exhibition essay by Paul D’Agostino for M. David Studio Residency

The culmination of weeks of planning and a ten-day, intensive on-site period of residency in Brooklyn, Exquisite Corpse will amount to a collective installation of works by Deborah Kapoor, Winston Mascarenhas, Bonny Leibowitz and Francesca Schwartz, all of whom find inspiration in various understandings and expressions of the body, and of bodies. This is a subject they examine and represent with marked abstraction, in visual terms, and conceptually as something internal, external, protean and interactive — and as the means for and locus of invasion and trauma, healing and recovery, stillness and grace.

The layout that curator and residency director Michael David currently envisions for this exhibit of ambitious new works by all four artists is based to some extent on counterbalances and junctures, perhaps not unlike certain aspects of bodily structures themselves. This should be considered in material as well as conceptual terms, not least with regard to how the four artists’ works will be spatially though somewhat casually paired: two artists will be installing their pieces primarily in the gallery’s front area, the other two toward the back. On the one hand, the idea is to create two separate spheres of bodily or meta-bodily expressions; on the other hand, it is to see what kinds of unexpected equilibrium might be attained as a result.

Filling in and encircling the gallery’s front space with airs of dynamism and spareness will be projects by Deborah Kapoor and Bonny Leibowitz, who have been working with one another’s pieces in mind without necessarily reacting to them. Working now in a minimalist, whispery palette, and with a set of materials somewhat new to her, Leibowitz will complete a sequence of sculptural works hanging from the ceiling. Delicate, airy and slightly astir, Leibowitz’s works will suggest internal tissues and physiological networkings, or perhaps extra-bodily transplants or spiritual emissions. Kapoor, meanwhile, taking cues from birds’ flight patterns and readings thereof, is planning to complete an array of small, variably abstracted, heavily mixed-media wall sculptures intended to surround, perhaps somewhat scavenger-like, Leibowitz’s pendant pieces. Small individually yet imbued with material gravity, Kapoor’s works will cohere with one another visually as a circling flock of abstract objects, or as a composite body composed of an array of bird-like bodies.

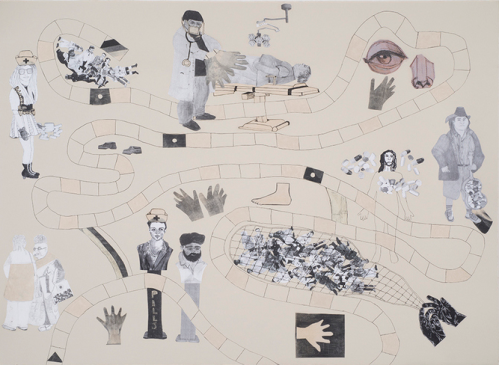

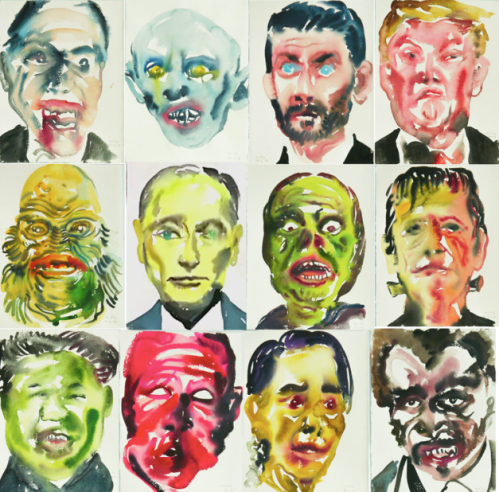

Francesca Schwartz and Winston Mascarenhas will present 2D and 3D works that explore notions of the body in ways both far more literal and markedly more abstract. In an extensive suite of variably sized mixed media paintings on handmade composite panels, Mascarenhas will encourage viewers to look at and consider not a body, but our bodies, hoping to communicate how so many of our corporeal and identity-related trappings make us all quite the same, while also individuating us within the very same sameness. In other words, he’ll be creating a series of textures and hues suggestive of our organs — large and small, internal and external — such as our hearts and, primarily, skin. As a retired physician, Mascarenhas certainly knows a thing or two about how we’re all made of the same stuff, and about how our hearts, the things that truly make us tick, were never designed to house the harmful biases that we might harbor in our minds. A practicing psychoanalyst, Schwartz certainly knows a thing or two about how and why we come to greater or lesser understandings of ourselves as individuals, and about how experiences of pain, trauma, anxiety and grief can inflect, inform, confuse, inhibit or enhance these same understandings. Although Schwartz brings a wealth of clinical expertise to the planning of her works, she tends to eschew any imaginable clinicality of style or approach in her assemblage-heavy pieces that incorporate photographs, texts, textiles, and a range of drawing and painting media as well as — since she’s also trained as a butcher — bones. Schwartz will present several manifestations of all such types of work.

A great deal of new art is being made for Exquisite Corpse. A great deal more has yet to be made. Soon it will all come together in the same space to be completed, tweaked and reworked. We’re all eager to see how the envisioned counterbalances and junctures take shape as an exhibition. And of course, we’re very eager to share all of these results with you.

________________

This essay was composed for Exquisite Corpse, an exhibition produced by M. David Studio Residency. It was on view from 9/28/2018 – 9/30/2018 at 56 Bogart Street in Brooklyn, New York City.

Paul D’Agostino, Ph.D. is an artist, writer, translator, curator and professor living in Bushwick, Brooklyn. More information about him is available here, and you can find him as @postuccio on Instagram and Twitter.